Charlie Parker on "Fine and Dandy" (1947–1953)

On the topic of concision in Bird's playing, Howard McGhee is quoted as saying:

Bird came up in the swing era, playing in big bands and crafting brief but complete solo statements to fit the compact demands of both live and recorded formats. At the same time, similar to the mythology surrounding early Lester Young in Kansas City, there's an aura surrounding the image of Bird in flight, stretching out with chorus after chorus of inspired blowing outside the confines of the recording studio.

The longest recorded solo of Bird's that I'm aware of is "Lester Leaps In" from the September '52 concert at the Rockland Palace Ballroom, which clocks in at nine choruses. I haven't done a careful study of this, but the longest blues solo I'm aware of is the "Happy Bird Blues," which is 14 choruses and is attributed to an after-hour jam session at Christy's Restaurant in Framingham, MA from April '51 (similarly extended blues performances include "Cool Blues" from a Jamaica, Queens concert in March '52 and a "Cool Blues" from the Open Door in NYC in July '53, both 13 choruses if I'm remembering right).

Bird was clearly sensitive to different performance contexts and adjusted accordingly; on recordings and radio broadcasts, he could shape the arc of his solo to meet the length constraints, but when playing with musicians in private or in more relaxed public settings, he took as many choruses as he wanted.

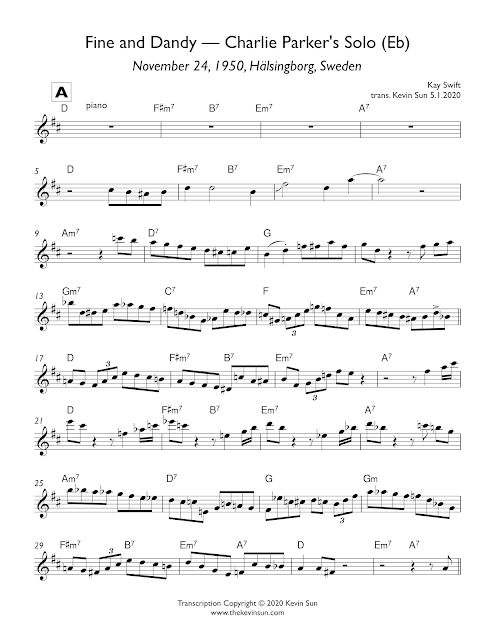

One of the common practice tunes that shows up multiple times in Bird's discography is "Fine and Dandy," a popular song published in 1930. No recordings exist of him performing the piece with any of his working bands, so it's interesting to hear how he navigates the jam session staple again and again between 1947 and 1953, which include several notably long improvisations, as well as instances where he takes two long solos during the same performance of the tune.

#1: Mutual Studios, NYC, September 13, 1947

Recorded for an all-star radio broadcast in the first few months after Bird's return to New York '47, he has time for just one chorus to lead off the solos. This was the first of several "Battle of the Bands"-type broadcasts that featured a double bill of bebop modernists and New Orleans-style "traditionalists." The band here included Bird, Dizzy Gillespie, John LaPorta on clarinet in the frontline, with Lennie Tristano, Billy Bauer, Ray Brown, and Max Roach in the rhythm section.

In Yardbird Suite, Lawrence Koch suggests that the tune might have been Tristano's suggestion: "...it was one of his favorite vehicles, and his Blue Boy, recorded in May of this same year, is based on the same chord structure."

Tristano's comping is notably aggressive here, but it doesn't seem to have much of an effect on Bird, who, despite being farther from the mic, is still clearly heard playing over the changes with characteristically immaculate voice-leading. Although the second bar of the 'A' sections is usually biii diminished, Bird invariably plays some variant of iii-VI there.

As a note, this was recorded just two weeks before his astounding guest appearance at Carnegie Hall with Dizzy Gillespie, where he was first recorded playing "Confirmation."

PDF downloads: C (treble) – C (bass) – Bb – Eb

In Yardbird Suite, Lawrence Koch suggests that the tune might have been Tristano's suggestion: "...it was one of his favorite vehicles, and his Blue Boy, recorded in May of this same year, is based on the same chord structure."

Tristano's comping is notably aggressive here, but it doesn't seem to have much of an effect on Bird, who, despite being farther from the mic, is still clearly heard playing over the changes with characteristically immaculate voice-leading. Although the second bar of the 'A' sections is usually biii diminished, Bird invariably plays some variant of iii-VI there.

As a note, this was recorded just two weeks before his astounding guest appearance at Carnegie Hall with Dizzy Gillespie, where he was first recorded playing "Confirmation."

PDF downloads: C (treble) – C (bass) – Bb – Eb

#2: William Henry Apartments, NYC, May 28, 1950

From Yardbird Suite:

Around the time of the Cafe Society booking, Bird attended several Sunday sessions at the William Henry apartment building at 136th Street and Broadway; the sessions were recorded by some of the other participants [according to Peter Losin, the tape from May was recorded by Gers Yowell, while the June tape was recorded by Jimmy Knepper or Don Lanphere]. The six-story building, terraced with fire escapes and housing a storefront, contained a sub-basement one-room apartment that was sought after by musicians because of its soundproof location; it was sometimes sublet to other musicians if the tenant or tenants were on the road. Tenorists Gers Yowell (who lived in the one-room pad with trombonist Jimmy Knepper and altoist Joe Maini during 1950) and Don Lanphere later found their copies of the session tapes and made them available commercially.

Maini, Knepper, and Lanphere were all in the Roland experimental band with Bird, and some other session participants were also from that group. The sessions were probably organized through this familiarity.Miguel Zenón first brought my attention to these recordings, and they're some of Bird's most inventive and lengthy documented improvisations; he's playing with and for musicians—with no time constraints—and he seems to be perfectly at ease and having a good time. Recorded just a week before the famous June 6, 1950 studio recording with Dizzy, Monk, Curley Russell, and Buddy Rich, this is prime Bird. There's a rawness and unevenness to the sound and articulation here that's generally refined away or smoothed out during his middle and later studio recordings, and the sustained fluency and unerring intensity is remarkable.

My recording was pitched up 1.5 half steps and insanely fast, so I adjusted it with Audacity, but it's still a burning tempo at which to play a five-chorus solo followed by another five-chorus solo to close out the tune (really, it's more like six choruses on both ends, since Bird blows through the melody statement played by the other horns during the opening and final choruses.)

There are numerous times where, despite the tempo, Bird manages to cram into double-time runs that resolve perfectly while setting him up for his next phrase. His third chorus starts with an exercise-like pattern that shows up in other recordings of tunes in F (including the "Happy Bird Blues") when he's turning up the heat during his solo, and it's not dissimilar to the kinds of diatonic patterns Coltrane would explore at length during his earlier period.

If anything, Bird's second solo is even more adventurous than his first. In the third chorus of that solo, he slips in the intervallic minor third-major third pattern that Carl Woideck discusses at length in Charlie Parker: His Music and His Life (pages 186-188), where he points out that the chromatic and harmonically ambiguous sequence shares a notable resemblance with Coltrane's later work and is even found in Slonimsky's Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns (#629). Woideck carefully points out that Bird was playing this pattern even before the book came out in 1947, as it shows up during a January '46 Jazz at the Philharmonic recording on "After You've Gone."

For comparison, this recording is dated roughly around or after the time of Bird's immortal Birdland appearance(s) with Fats Navarro and Bud Powell, collected on One Night at Birdland (see here for Bird's solo on "Ornithology" and Powell's solo on "'Round Midnight").

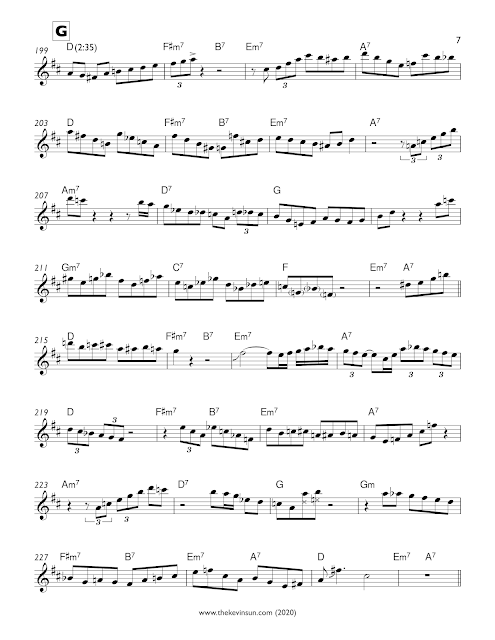

#3: Hälsingborg, Sweden, November 24, 1950

Six months after the apartment session and a year and a half after Bird's triumphant European debut in Paris, he went to Sweden for a weeklong tour where he worked as a single with capable local rhythm sections. He was enthusiastically received there, as can be heard on the recording from this post-gig jam session at a restaurant in Hälsingborg.

Being in a foreign place and playing with new musicians, Bird seems content to go with the flow. On a gig recorded two days before, he and his Swedish All-Stars gave the only documented performance of "Cheers" from Bird's early Dial days, which most likely was a request. On "Scrapple from the Apple" from the earlier gig on the same night as the jam session, the rhythm section inadvertently plays the bridge from "Honeysuckle Rose," which Bird immediately adapts rather than tipping them off to the rhythm changes bridge that goes with the tune.

The tempo is a bit slower than on both of the earlier recordings, and the lines have a more even, relaxed quality to them than on from the apartment session recording. Toward the end of the second chorus, Bird lets out a high pitched cry and then leads into the next chorus with an emphatic repeated sustain on F, something that he does on other recordings but seems to prolong more here, like he's communicating something to the musicians or to the audience.

There's an edit immediately after Bird's first five-chorus solo that leads to the top of his second helping (it sounds like somebody's saying "head out" and a tenor comes in briefly, but it sounds like somebody says the same thing shortly after that, so maybe it's just a word in Swedish). At a few points in the second solo, Bird notably eases into the lowest range of the horn before returning back up gradually, and he trades for two choruses with trumpeter Rolf Ericsson, who sounds good with Bird throughout his Swedish tour.

Finally, as an Easter egg during out head, he slips in "Little Willie Leaps" during the second half.

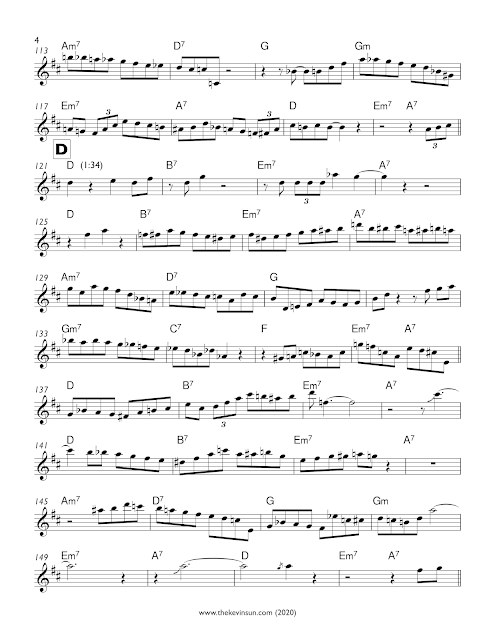

#4: Pershing Hotel Ballroom, Chicago, February 11, 1951

The next recording of Bird playing over these changes comes just a few months later, this time at Chicago's Pershing Hotel Ballroom with a Chicago rhythm section: Claude McLin on tenor, George Freeman on guitar, Chris Anderson on piano, Leroy Jackson on bass, and Bruz Freeman on drums. The gig was on a Sunday; Bird had just opened an 8-day run with strings in Pittsburgh at a venue called Johnny Brown's, with four shows per day (an afternoon matinee and three evening shows on Saturday, with four evening shows during the week starting from 8:30 PM to 1:00 AM, according to Ken Vail's Bird's Diary), and he flew to Chicago to make this on his one off-night.

I first heard this recording on a 23-part series on Phil Schaap's Bird Flight (archived at his website, beginning June 12, 2013 through July 17, 2013), where he focuses on a series of one nighters from 1950 and 1951 where Bird takes multiple long solos on the same tune. Schaap suggests that the repetitiousness and frequency of his strings performances around this time could be a cause for Bird's unusually extensive improvising documented during this period, which doesn't re-occur before or after in his discography.

Schaap starts with the night of Bird's 30th birthday at the Rainbow Inn in New Brunswick, NJ, which came shortly after Bird's engagement at the Apollo that same August. Six shows from one day were recorded by Al Porcino, Don Lanphere, and Jimmy Knepper, all with the same set in the same order: "Repetition," "April in Paris," "Easy to Love," and "What Is This Thing Called Love," the repetitiousness of which Schaap memorably gets across by reciting the set list over and over.

Schaap starts with the night of Bird's 30th birthday at the Rainbow Inn in New Brunswick, NJ, which came shortly after Bird's engagement at the Apollo that same August. Six shows from one day were recorded by Al Porcino, Don Lanphere, and Jimmy Knepper, all with the same set in the same order: "Repetition," "April in Paris," "Easy to Love," and "What Is This Thing Called Love," the repetitiousness of which Schaap memorably gets across by reciting the set list over and over.

On this night, Bird is going along with the band in terms of repertoire, with a unique recorded performance of the Rodgers and Hart standard "There's a Small Hotel," the Woody Herman head on "Fine and Dandy" entitled "Keen and Peachy," Claude McLin's rhythm changes head "Swivel Hips," and a set-concluding "Goodbye."

The tape opens during the second eight bars of Bird's improvised chorus, and he follows that with a full six choruses. Early in the series, Schaap suggested that this might be Bird's longest recorded solo, at which point I decided to transcribe it and repurpose the material for a composition, but a few broadcasts later, Schaap corrected himself and noted that "Lester Leaps In" was at least one instance of a longer solo.

Still, this is Bird's longest recorded improvisation on this tune, and his sound and execution are outstandingly clean and precise. About the same tempo as the apartment sessions recording, it's harder to make out the rhythm section in this ballroom recording, but the rhythm section sounds a bit lighter, which in turn seems to let Bird play longer and lighter, including a few phrases stretching out to a full eight bars.

At the top of a few choruses, Bird plays a phrase that seems to be a quote (third and fifth chorus, or C and E on the transcription), and which also turns up on the Sweden recording. There's an audible uproar as he leads into the fifth chorus and plays the phrase, which calls to mind something Dizzy Gillespie mentioned in DownBeat in 1961 (via Woideck's Charlie Parker):

The tape opens during the second eight bars of Bird's improvised chorus, and he follows that with a full six choruses. Early in the series, Schaap suggested that this might be Bird's longest recorded solo, at which point I decided to transcribe it and repurpose the material for a composition, but a few broadcasts later, Schaap corrected himself and noted that "Lester Leaps In" was at least one instance of a longer solo.

Still, this is Bird's longest recorded improvisation on this tune, and his sound and execution are outstandingly clean and precise. About the same tempo as the apartment sessions recording, it's harder to make out the rhythm section in this ballroom recording, but the rhythm section sounds a bit lighter, which in turn seems to let Bird play longer and lighter, including a few phrases stretching out to a full eight bars.

At the top of a few choruses, Bird plays a phrase that seems to be a quote (third and fifth chorus, or C and E on the transcription), and which also turns up on the Sweden recording. There's an audible uproar as he leads into the fifth chorus and plays the phrase, which calls to mind something Dizzy Gillespie mentioned in DownBeat in 1961 (via Woideck's Charlie Parker):

I saw something remarkable one time. He didn't show up for a dance he was supposed to play in Detroit. I was in town, and they asked me to play instead. I went up there, and we started playing. Then I heard this big roar, and Charlie Parker had come in and started playing. He'd play a phrase, and people might never have heard it before. But he'd start it, and the people would finish it with him, humming.Brian Priestley adds in Chasin' the Bird that Ira Gitler had noticed the same thing at the Pershing Ballroom in the late 1940s (from the liner notes to The Complete Savoy and Dial Studio Recordings, which I don't have on hand).

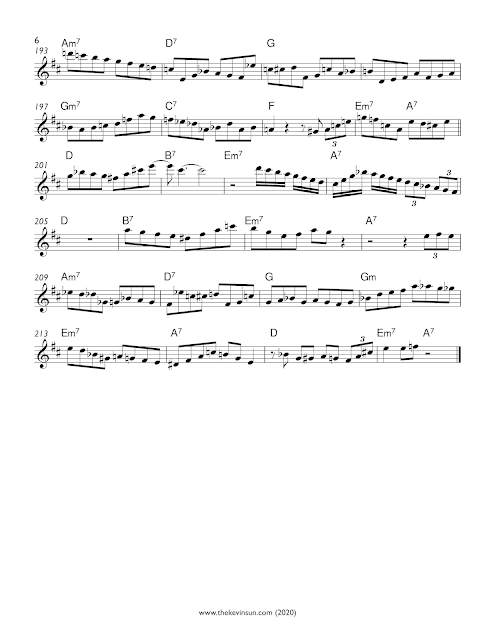

#5: Club Kavakos, DC, February 22, 1953

Bird lost his cabaret card in July 1951 following a drug bust, which forced him to make money with out-of-town gigging and touring. A series of issues between Bird, club owners, and his management put him in financial trouble, and by early 1953, he resorted to playing illegally in New York without his cabaret card. In Chuck Haddix's The Life and Music of Charlie Parker, Bird's letter to the State Liquor Authority is reproduced:

My right to pursue my chosen profession has been taken away, and my wife and three children who are innocent of any wrongdoing are suffering... My baby girl is a city case in the hospital because her health has been neglected since we hadn't the necessary doctor fees...I feel sure when you examine my record and see that I have made a sincere effort to become a family man and a good citizen, you will reconsider. If by any chance you feel I haven't paid my debt to society, by all means let me do so and give me and my family back the right to live.

Bird was ultimately successful in getting his cabaret card reinstated, but during this period, he seemed to be facing potentially significant financial challenges. Just a week after illegally opening at a large new venue called the Band Box next to Birdland, he agreed to a one-nighter with a big band at a venue in DC called Club Kavakos on February 22, 1953, reportedly for a flat fee of $50 according to Vail (approximately $480 today), which would have been far below Bird's regular rate compared to his other gigs around the same time.

The recording is thrilling, with Bird playing over unfamiliar arrangements and responding on the fly, including catching a key change on the changes to "Out of Nowhere" in the blink of an eye. Koch gives some context for the ensemble and the circumstances surrounding Parker's appearance:

The recording is thrilling, with Bird playing over unfamiliar arrangements and responding on the fly, including catching a key change on the changes to "Out of Nowhere" in the blink of an eye. Koch gives some context for the ensemble and the circumstances surrounding Parker's appearance:

"The Orchestra" was the brainchild of drummer-arranger Joe Time and several other Washington musicians. Conover, however, long associated with the Voice of America jazz broadcasts, provided the clout to present the band publicly. In 1953 the group had been existence for about a year and a half and was soliciting guest soloists such as Gillespie and Stan Getz. But because of Parker's poor reputation for meeting his professional obligations during this period, Conover decided to do no advertising of Parker's guest shot other than word-of-mouth rumors that Bird might appear. All the same, Parker did appear—although not in time for rehearsal—and roared through the complex arrangements by Al Cohn, Gerry Mulligan, Johnny Mandel, and others.

Of the five recordings of "Fine and Dandy," this is the slowest at a medium up-tempo lope. This cut opens the recording, with the big band kicking off the melody in B with a multitude of substitutions and passing chords before modulating to the common practice key of F for Bird's three chorus solo. Compared to the Pershing recording two years earlier, Bird is audibly digging in more here, both because of the more moderate, swinging tempo and to match the volume of the big band's backgrounds on his opening chorus.

Interestingly, Bird seems to accommodate the biii diminished on the second bar of the A sections more often here than on previous recordings, although he continues to imply other changes (including the biii minor substitution leading to the third bar). The triplet "rocking" phrase at the end of the first chorus is unusually extended, but it functions perfectly as a dramatic gesture leading into the second chorus. He also slips in the cornet line from Scene III of Stravinsky's Petrushka (mm. 77-79 on the transcription), which is a favorite quote in his live recordings, as well as Charlie Shavers's "Dawn on the Desert" in the second chorus, which is an even more frequent quote (thanks to the website Chasin' the Bird and its extensive list of Bird quotes for helping me identify this).

There's a variety of phrasing, rhythmic ideas, and harmonic navigation in this solo that's fitting for its placement as the final entry of the piece in Bird's discography. Although he never recorded it formally for commercial release, the existing documents span a broad period of his mature career from his return to New York from LA to near the end of his life, in a range of settings that allow us to hear him from his most self-edited to his most relaxed and spontaneous.

Excellent. A pleasure to read. Thank you for your hard work. Bird lives!

ReplyDeleteFantastic- thank you!

ReplyDelete