Charlie Parker on "This Time The Dream's On Me" (1950–1953)

Of the tunes that Bird played live but never recorded in the studio, Harold

Arlen and Johnny Mercer's "This Time the Dream's On Me" is notable in that

Bird had prepared a quintet arrangement and was documented playing it in

both quartet and quintet formats over the years. Dean Benedetti recorded at

least three (possibly four)

live versions of Bird playing the tune at the Onyx in July 1948, where he

sounds rather tentative compared to the live recordings from 1950 through

1953.

Although Bird tended to (and was pressured to) record originals at his

small group recording dates, he did record a fair number of standards in his

later period, including "The Song is You, "I Remember You," "Why Do I Love

You," and "I'm in the Mood for Love." In Yardbird Suite, Lawrence

Koch cites the second AFM recording ban that stretched from January 1948

until mid-December 1948 as a possible reason why Bird never recorded the

tune, although that didn't stop him from going into the studio twice in

September '48 to record sets of originals, notably "Marmaduke,"

"Ah-Leu-Cha," "Parker's Mood," and "Barbados," among others.

Bird probably heard the tune when it first appeared in Blues in the Night (1941) at the movies, the same way many other musicians found new material over the years (Ethan Iverson shares a telling anecdote from Ron Carter about learning "The Shadow of Your Smile" by watching The Sandpiper in the theater). On a contrasting note, in a blog post by Martin Westin, apparent first-hand accounts exist of Bird going to the movies during his November 1950 trip and falling asleep (not confirmed by other published sources as far as I know, so I can't speak to the veracity of the account, but there are a lot of detailed stories in Westin's post). In any case, Bird like many other mid-century improvisers was game to adapt contemporary popular material for his working band; his interpretations of "A Slow Boat to China" is a illustration of this, where he is documented playing them on the Roost broadcasts in late 1948, the same year the song was published.

"This Time the Dream's On Me" would have been a fine candidate for a studio recording, and fortunately for us, the four live recordings that survive from 1950 through 1953 are substantive and illuminating. (On a related note, "Stardust" is a far more well-known standard that Bird played live numerous times—at least four semi-complete versions and numerous fragments between 1947 and 1952—that regrettably was never captured in the studio; however, the private tapes with him playing lead alto in Gene Roland's +20-piece big band and the Rockland Palace version with string arrangement are ravishing and unique in their own right).

Notably, all four versions in the '50s feature Bird with either his working band or a band of all-star colleagues, and they all were documented close to home in Manhattan and Brooklyn. In two cases, Bird is playing in a large room for dancers, and the choice of songbook repertoire from those gigs shows his sensitivity to the goings-on, which doesn't necessarily preclude him from lengthy flights of double-timing as well as high-velocity exchanges with the drums. The two versions without a second horn also feature extensive blowing and trading; as much as I like the quicksilver two-horn sound when phrasing unison melodies with Dizzy et al., I feel like he stretches out with greater abandon sometimes when left alone in the front line. (Even fewer "trio" recordings of Bird exist where the pianist lays out, as I often wonder what a studio date with bass and drums only would have been like had he been around in the later '50s, when that format became more widely recorded.)

Although I haven't heard this tune called much at jam sessions in the city, there seem to be plenty of notable instrumental recordings of this tune over the years. In the '50s, both Paul Bley and Kenny Burrell selected the tune—with Bird's hits during the head, and in Burrell's case, with even more hits on the bridge—for their respective Introducing albums. Burrell even has drum kit and conga trading on his version with Kenny Clarke and Candido Camero—the same percussion duo no less on Parker's May 9, 1953 broadcast at Birdland, where Candido has a lengthy solo on "Broadway." Another Birdland broadcast later that month, Candido and Art Taylor play together unaccompanied on "Moose the Mooche."

The tune was also recorded but not initially released on first of the two sessions that produced The Max Roach 4 Plays Charlie Parker, which features another Bird alumnus, Kenny Dorham. The recently deceased Larry Willis recorded a poignant version of "This Time the Dream's On Me" for a solo piano album of the same name in 2011, and Sir Roland Hanna also recorded a trio version shortly before his passing in 2001. There's even an aircheck (which I haven't heard) of the Basie band playing the tune in October 1941, the same year as the film release, at the Cafe Society Uptown, which includes none other than Klook at the drums filling in for Jo Jones.

#1: May 17, 1950, Birdland, NYC

This broadcast from half a year after Birdland's opening is widely considered one of the pinnacles of recorded live bebop: Bird, Fats Navarro, Bud Powell, Curley Russell, and Art Blakey. Bird and Fats clearly inspire one another in their trades, while Bud's molten inventions often threaten to steal the show from under the horns.This is the era of Parker approaching the peak of his stardom, with the opening of his eponymously named club a few months earlier as well as the release of Charlie Parker with Strings in February 1950. It was around this time that Bird also seemed to settled on the horn set-up that defined his mid- to late-period recordings: a King Super-20 with a sterling silver bell (notoriously difficult to solder to the rest of the instrument, as technician George Yao of the New Bamboo sax shop in Shanghai pointed out to me) and his named engraved on the bow-to-bell joint (Chuck Haddix notes Bird's endorsement in the January 1950 issue of Metronome magazine: "King really came up with THE horn").

Bird also seemed to settle on a now extremely rare mouthpiece around this time through the rest of his life, a Selmer England metal mouthpiece. Nicolas Trefeil details Bird's mouthpieces here, and helpful additional photos and notes are on the Japanese website Charlie Parker Laboratory. I've never encountered one of these in person and would be curious to take a look at the design, including the baffle shape and chamber size, but it seems very likely that this was the exact set-up he used on Charlie Parker with Strings based on this session photograph.

In additional to acquiring a measure of stability in terms of his instrument, Haddix also mentions Bird's happiness in his more settled family life after Chan and her daughter Kim moved in with him in late May 1950. Given this relatively newfound consistency, Bird sounds completely at liberty to stretch on these Birdland recordings, and this first version of "This Time the Dream's On Me" has Fats Navarro either laying out or absent from the date (if multiple), giving Parker room to phrase the melody as he pleases before launching into a two-chorus solo.

There's a fleeting intimation of the Blue Danube waltz at the top of the first bridge, and before that, he seems to quote another classical passage just after his solo break (does anyone recognize this?). Bird doesn't waste any time diving into extended double-time runs, which punctuate the eighth note phrases throughout both choruses, while he seems content to play the bridge fairly straight as Bud slips in some chromatic alterations. The undeniable bounce of Art Blakey's ride cymbal complements Bird marvelously; note the fill and thunderous crash leading into the second chorus. He responds in kind during drum trades with spirited ideas, including an interesting open-interval shape on the second A of the trading. This track is just one of the many highlights from the Birdland recordings with this remarkable configuration.

Note: There has been a lot of discographical uncertainty surrounding this date or dates, which wasn't helped by Columbia issuing parts of it as One Night in Birdland, dated June 30, 1950, a week before Fats Navarro's far too early passing. I'm using the Boris Rose date here.

Note 2: I also wrote briefly about "Ornithology" from this recording here, which links to Steve Coleman's in-depth analysis of the same performance.

PDF downloads: C (treble) – C (bass) – Bb – Eb

#2: June 23, 1951, Eastern Parkway Ballroom, Brooklyn

On the first of the quintet versions since the Benedetti fragments from '48, Bird plays the harmony part to the trumpet's melody before playing the bridge himself. Around this time, Bird had been playing more extensively with the working Bird with Strings format, but he also continued to perform with his quintet, with notable recordings from (possibly) the Symphony Ballroom in Boston in April '51 (more on that on "Confirmation" from the same performance). Around this time, he also began a period of taking longer and/or multiple solos on a single song, documented early on during the April 12, 1951 jam session recording at Christy's Restaurant in Framingham, MA.This recording, the only one that survives of Bird performing in Brooklyn, has rather poor fidelity and sounds distant, which provides a sense of the size of the Eastern Parkway Ballroom the band was working in. By this point, Walter Bishop Jr. and Teddy Kotick had replaced Al Haig and Tommy Potter in the working quintet, and this recording captures Benny Harris in place of Red Rodney, which would continue on and off for some time thereafter; Roy Haynes continues to hold down the drum throne.

As with the 1950 Birdland performance, Bird uses more or less the same double-time solo break. This recalls his precomposed famous break on "A Night in Tunisia," whose recurrence and association with the piece led Henry Martin to give the break its own designation as a kind of standalone composition (likened to a repertorial cadenza) in his interesting recent study, Charlie Parker, Composer. It's even in the same key, but Bird doesn't reproduce the break in the remaining two live recordings, although it seems likely that this might have been prepared with a possible studio recording in mind.

The ballroom setting doesn't seem to discourage Bird in any way from playing immaculate double-time runs, but the overall setting seems more relaxed than at Birdland. He follows phrase after phrase with beautifully voice-led melodic shapes, including his favored upper extension arpeggiations on the second bridge over a series of dominant 7ths.

PDF downloads: C (treble) – C (bass) – Bb – Eb

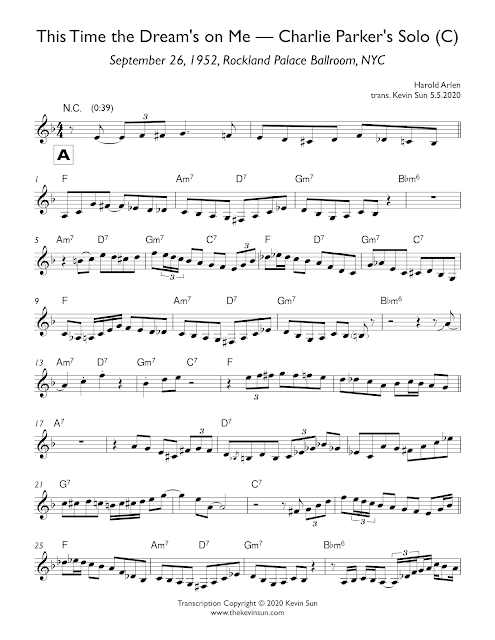

#3: September 26, 1952, Rockland Palace Ballroom, NYC

On this recording, the '50 Birdland recording, and one of the Benedetti recordings, Bird deals with a perennial source of irritation for saxophonist: his G# key sticks, and in this case on an important melody note during the bridge. As he shows repeatedly throughout his recorded career—most notably on the video of "Hot House" with Bird and Diz, where he reaches up with his left hand to unstick the octave key in the three beats during the last bar of the second A before the pickup to the bridge—Bird recovers almost instantaneously before soldiering along, taking four full choruses later followed by two choruses of trading with Roy.Koch puts it neatly in Yardbird Suite when he writes, "Bird, however, is wailing like a wild auk; he sends ideas flying crazily, both on his solo and in a set of two-chorus exchanges with Haynes."

I was somewhat surprised when I realized that this track was one of the live recordings selected for use in the heinously overdubbed soundtrack of Bird, but this piece of reportage from Peter Watrous in the New York Times from 1988 explained things:

''We had a problem,'' Mr. Eastwood explained. ''We needed longer takes for the performance shots, and the studio takes, which sounded fair, were too short. So we went after Parker's live performances.'' ... One of the elements guiding the choice of Parker material for the movie was Mr. Eastwood's desire to use several solos that had either never been heard before or that were rare ''so that the real aficionados who know the history would have something special,'' he said.

Along with "Lester Leaps In" from this date being the (possibly) longest Bird solo on record, this is his longest solo on this tune, with Parker stretching out over the changes of this now long-familiar vehicle. The tune is taken at a brighter tempo than at the dance in Brooklyn from the year before, and a shape on the 8th bar of the first chorus is one that seems particular to his playing in F at fast tempos (see the May 28, 1950 performance of "Fine and Dandy," among others).

Just as he was renowned early on for being able to navigate the channel, or bridge, of "Cherokee" with elegant voice-led lines, Bird also makes the most of the rhythm changes bridges here, reprising the upper extensions figure on the second bridge while modulating a tuneful motif throughout the third bridge. There are apparently multiple sources for the recording of this performance, with Chan's tape being the primary source, and it sounds like the tape source does change during this tune at the end of his solo and again during the beginning of the trading, but we're of course fortunate to have this document at all. The way Bird immediately returns Roy's triple-meter figure during the second bridge of the trading is timeless.

PDF downloads: C (treble) – C (bass) – Bb – Eb

#4: July 26, 1953, Open Door, NYC

Recorded just four days before the hour-long studio session that produced immortal versions of "Confirmation," "Now's the Time," "Chi-Chi," and "I Remember You," the last recording of Bird playing "This Time the Dream's on Me" finds him once again playing with a band of high-level bebop colleagues: Benny Harris, Al Haig, Charles Mingus, and Art Taylor (personnel according to the Peter Losin discography, and Phil Schaap gives the story of the session in the liner notes to Bird: The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve box set).July 26, 1953 was a Sunday night, and Bird would have been appearing as part of the jam session series produced by Robert Reisner. Reisner includes a colorful account of this period in his preface to Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker, an invaluable document of primary source remembrances by musician colleagues, family, and friends.

I'm not sure if this date was actually a jam session or not, though, since the four sets recorded by Chan only document some of the heads and Bird's solos, but the repertoire seems to belong solidly to Bird's working band format, so it might just have been a regular Parker-led date. This is late Bird nearing the end of his best work from this time, including the aforementioned studio date, some performances at Birdland and the Hi-Hat in Boston, and the famous May 15, 1953 all-star quintet performance at Massey Hall in Toronto.

It's clear that from this recording and those from '52 and '50 that part of the arrangement included squeezing an altissimo concert C into the melody. It's always on the last A section of the melody (in head from '50, out head of '52 and here), and although it speaks loud and clear on the earlier recordings, he cracks the note this time. Audio clip plays the relevant part of the melody from '50, '52, and '53 in that order:

There's also some confusion during the drum trading when Bird seems to cue the out-head after at least (probably) two choruses of trading: In the heat of the moment, it seems like the downbeat might get lost beneath Roy's explosive drumming. Bird seems to just play the next few bars as Roy switches to the hits on the head, and the trading continues for another chorus.

Despite these minor snafus, it's a solid late-period performance with relatively little double-timing. Bird seems content to ride the wave of the rhythm section, and he spills into Roy's four bars on the second bridge of the trading, echoing and answering his own calls.

PDF downloads: C (treble) – C (bass) – Bb – Eb

* * * * *

Just a month before this recording, Bird appeared optimistic about the future in his interview on WHDH with John McLellan (recorded around the time of his run at the Hi-Hat). It's here that he gives his most complete verbalized statement of his creative philosophy to date: lived experience as the basis for expression.

John McLellan: What about your own group—the people you work

with, the other musicians who started with you? I've noticed that, for

example, you play "Anthropology" and "52nd Street Theme," perhaps, but

they were written a long time ago. What is to take their place and be the

basis for your future?

Charlie Parker: Hmm, that's hard to tell, too, John. You see, your ideas change as you grow older. Most people fail to realize that most of the things they hear coming out of a man's horn—ad lib or else things that are written, you know, say, original things—I mean, they're just experiences, the way he feels: The beauty of the weather, the nice look of a mountain, or maybe a nice, fresh cool breath of air. I mean all those things—you can never tell what you'll be thinking tomorrow, but I definitely say that music won't stop. It'll keep going forward.

JM: And you feel that you, yourself change continuously?

CP: I do feel that way, yes.

JM: And in listening to your earlier recordings, you become dissatisfied with them? You feel that...

CP: I still think that the best record is yet to be made, if that's what you mean.

* * * * *

Somewhere, someday

We'll be close together, wait and see

Oh, by the way

This time the dream's on me

You take my hand

And you look at me adoringly

But as things stand

This time the dream's on me

It would be fun

To be certain that I'm the one

To know that I, at least, supply the shoulder you cry upon

To see you through

Till you're everything you want to be

It can't be true, but

This time the dream's on me

We'll be close together, wait and see

Oh, by the way

This time the dream's on me

You take my hand

And you look at me adoringly

But as things stand

This time the dream's on me

It would be fun

To be certain that I'm the one

To know that I, at least, supply the shoulder you cry upon

To see you through

Till you're everything you want to be

It can't be true, but

This time the dream's on me

Comments

Post a Comment